Simply asking questions is not enough to understand the people we serve. Effective research and responsible design require more thoughtful, grounded ways of getting to know users, learners and clients. In this piece, Prof. John Traxler reflects on the limitations of familiar methods and explores alternative approaches to uncover values, feelings and knowledge that are often difficult to articulate. He further examines the ethical and methodological assumptions that shape how we gather and interpret insight.

Exploring People’s Values, Feelings and Knowledge Beyond Traditional Methods

Author: Prof John Traxler, UNESCO Chair, Commonwealth of Learning Chair and Academic Director of the Avallain Lab

The Challenge

St. Gallen, February 23, 2026 – We all want, or we all need to know about the feelings, knowledge and values of other people. So how do we get answers? We ask them questions. Is this a good idea? No, rarely, and this piece explains why and the broader scope of any findings or conclusions. If it were even possible that the people concerned gave accurate, complete and trustworthy answers, does this tell us anything at all about the views, feelings or knowledge of any other people, in any other place, at any other time?

Someone once observed that much accepted psychological theory is based on research using psychology undergraduate subjects because such subjects are the nearest, cheapest and easiest for university-based academics conducting psychological research. That is not necessarily a good basis for theories supposedly applicable to the rest of humanity. At an early age, Freud supposedly explained our inner workings, but did so based on a small number of case studies of some very ill people. Not a good evidence base.

The Usual Suspects and Their Defects

The ‘usual suspects’ are roughly interviews, semi-structured or otherwise, questionnaires, focus groups and surveys. They get routinely rounded up whenever anyone has a question that needs an answer. They do, however, have two overall problems, namely, firstly, that they will only get the answer to the question that they asked, nothing else, nothing more important, nothing more relevant, and secondly, the question or the questioning may be so flawed that they do not even really get that.

To be more specific, the people answering the question may not know what it means; they may misunderstand or misinterpret it; they may be uncomfortable answering it, uncomfortable disclosing their ignorance of the answer or uncomfortable with its implications; they may mishear or misread the question. They may be consciously or unconsciously needing to perform a particular identity or persona, to appear as knowledgeable, affable, professional, naive, superior, cautious, flirtatious, relaxed, important, distant or rushed, depending on the context and depending on their psychological needs and preferences, and thus only provide answers in line with that performance. These may only lead to changes in emphasis or tone, but can still be highly significant.

Why Answers Cannot Be Taken at Face Value

Examples come easily. People who use pornography but won’t admit to it, people who tell me my lecture was great but tell each other it was rubbish; people who give me any answer for fear of disappointing me with no answer, people who rush to reach the end of the survey or the end of the interview; people who don’t want to be different or conversely do really want to be different, and so on. In essence, people are not machines, and neither are these methods objective or scientific.

To take a step back from questions, we need to think about the different kinds of thoughts and feelings that people have and thus try to match our methods of enquiry to those different kinds of thoughts and feelings. Finding out about people’s aspirations is not the same as finding out about their height; finding out about the future is not the same as finding out about the past; finding out about their habits is not the same as finding out about their worries.

Furthermore, we all know things without realising we know them or without being able to clearly express them; being able to change manual gear, lace your shoes or play the guitar does not mean being able to recollect or explain them, they are intuitive, tacit or compiled; some activities and assumptions are unconscious or ‘hard-wired’ and a question will not produce a useful account or explanation. This means that questioning is not always effective, and a portfolio of alternative methods is needed, each appropriate to the type of knowledge, feeling or value being explored. We briefly mention some later, but in the context of procurement, perhaps models, role-play, simulation or prototypes are a more useful way of eliciting requirements than merely asking clients what they would like.

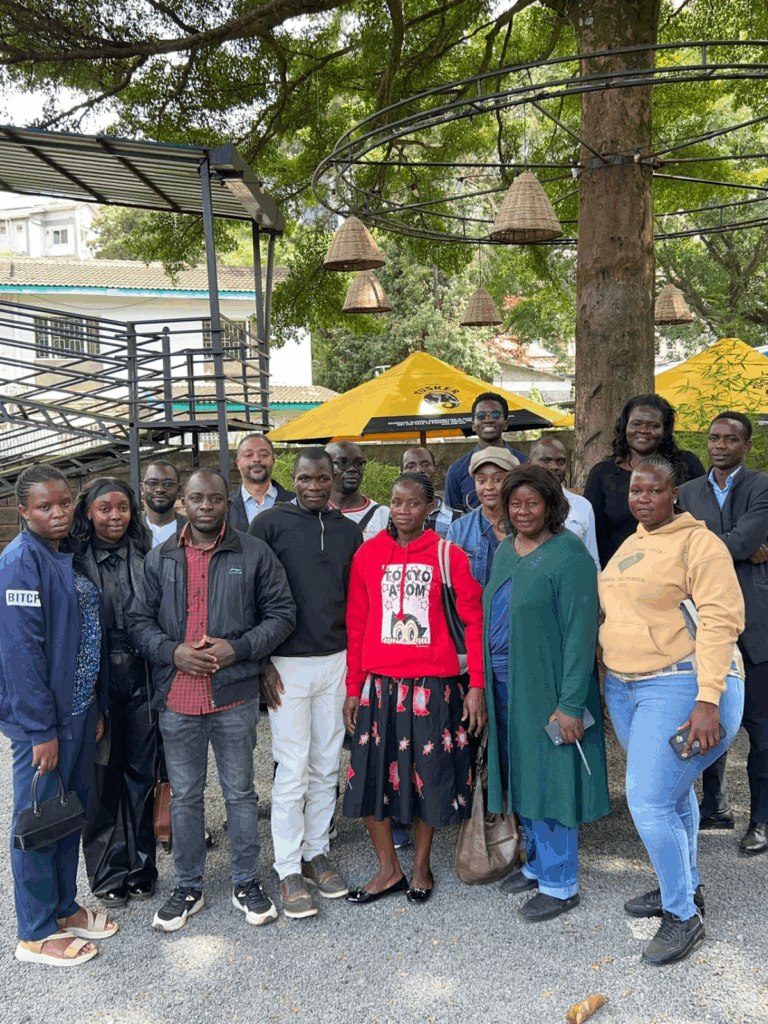

All of these concerns worsen as we attempt to question people more distant or different from ourselves, as do the ethical concerns, which is another reason for exploring a portfolio of alternative methods.

Methodological Limits and Ethical Concerns

The commonly used methods are not only methodologically problematic, in the sense that they are not necessarily trustworthy, but also ethically problematic. They privilege and empower the questioner, turning the people involved into passive data sources, and the greater the distance, the difference and the differential between the questioner and the people answering, the greater this ethical problem. Think only of middle-class professionals questioning working-class people, the employed questioning the jobless, men questioning women, Europeans questioning Africans, the neurotypical questioning the neurodiverse, the settled questioning the nomadic, the urban questioning the rural, the affluent questioning the poor and many other comparable dichotomies. These may be generalisations or simplifications, but the problem should be apparent even in less blatant situations.

There are a variety of common mistakes. Quantitative findings, based on statistics, usually provide precise percentage figures while overlooking small sample sizes and confounding contextual factors. Whilst qualitative findings based on interviews or focus groups can depend merely on ‘cherry-picking’ the most attractive and agreeable quotes to make their case.

There are tactical improvements, perhaps making the best of a bad job. The literature on interview structuring and questionnaire design can give enormous amounts of guidance. ‘Start with easy topics, don’t be too challenging too soon.’ ‘Don’t ask questions that are double negatives.’ ‘Don’t ask questions that have multiple clauses’, such as ‘do you like apples and oranges?’ or ‘do you not dislike pears?’. It is also important to think about changing the delivery or the setting to adapt to the barriers or challenges, and think about a proxy for the researcher nearer to the class or culture of the research participants.

The Usual Suspects and the Alternatives

OK, so if the ‘usual suspects’ are methodologically and ethically problematic, are there any alternatives? More to the point, are there any established, efficient, cheap and trustworthy alternatives? Luckily, the answer is ‘yes’, but context is the caveat and expertise and experience might be the prerequisites. By context, we mean that one-size-fits-all will not work; thus, expertise and experience are needed to make choices, allowances and adaptations that are context- and circumstance-dependent.

We can provide examples, but the underlying motivation is to provide a space and opportunity for people’s thoughts and feelings to emerge as candidly as possible. One stance that can help with this is Personal Construct Theory, PCT. This suggests that people are like scientists, creating unique mental frameworks called constructs, ways of seeing the world, to interpret and predict events in their lives, however trivial, embarrassing, superstitious, irrational, or mundane. Behaviour stemming from these personal understandings rather than from objective reality, these are ways to make a bit of sense of the worlds in which each lives. This, in turn, leads to a range of tools and techniques to elicit personal constructs and gain small insights into how each person understands the world.

Card sorts are one such tool, in which individuals repeatedly sort cards of images or ideas to identify underlying clusterings in how they perceive or apprehend them, without being asked for any rationalisation, explanation or justification. Card sorts, despite or because of their simplicity and efficiency, have an established track record in designing products and websites, accessing preferences and reactions that people cannot necessarily easily articulate. Laddering is a companion follow-up technique that repeatedly asks ‘why?’ to uncover the deeper foundations of preferences for the clusterings. Again, efficient, effective and cheap. Both are only slightly more sophisticated than these explanations suggest, but still ethically more acceptable than the ’usual suspects’ since the explanation is also not much more sophisticated, and consent really is ‘informed’.

Alternative Tools, Formats and Settings

There are others, from other academic or commercial sources, rich pictures, a way of community members or organisation members, say employees or clients, expressing alliances, affiliations, antagonisms, transactions and relationships, with just cartoonish drawings. Without them, any survey or focus group might be hopelessly naive about what is bubbling away under the surface.

Tackling the challenge from a different direction, it can be worth asking whether the formats by which communities or cultures interact and discuss might map onto a format that we as European researchers would already recognise; is the talking circle near enough to a focus group, for example, and can we meet in the middle with a little adaptation?

This suggests, of course, that the surroundings as well as the format are important, some more naturalistic, informal and relaxing than, say, a university office, interview room or laboratory, especially when video or audio recording can add extra intimidation. Some market researchers, for example, testing television advertisements, will mock up the apparently authentic living room of the target demographic audiences. This would be complete with a TV in the corner, pictures on the walls, tatty sofas, chairs, coffee tables and hidden cameras, before recruiting families to inhabit this ersatz living room and watch television programmes and un-self-consciously, the proposed advertisements.

So What Have We Learnt?

Clearly, don’t just round up the ‘usual suspects’. More positively, think about the nature of your enquiry and the nature of the people who can help with it. Consider the findings and your claims and avoid overselling them. Be brave, be eclectic, experiment, reflect and adapt, but build on what others have done and ask why they did it. It would be unwise not to explore how the expertise and experience captured, albeit imperfectly, by AI might at least allow us to explore permutations and possibilities, nudging our imaginations.

These efforts are, in the end, about understanding our users, learners and clients more fully in order to respond to them more appropriately and responsibly.

About Avallain

For more than two decades, Avallain has enabled publishers, institutions and educators to create and deliver world-class digital education products and programmes. Our award-winning solutions include Avallain Author, an AI-powered authoring tool, Avallain Magnet, a peerless LMS with integrated AI, and TeacherMatic, a ready-to-use AI toolkit created for and refined by educators.

Our technology meets the highest standards with accessibility and human-centred design at its core. Through Avallain Intelligence, our framework for the responsible use of AI in education, we empower our clients to unlock AI’s full potential, applied ethically and safely. Avallain is ISO/IEC 27001:2022 and SOC 2 Type 2 certified and a participant in the United Nations Global Compact.

Find out more at avallain.com

_

Contact:

Daniel Seuling

VP Client Relations & Marketing